For example the Cambo Actus bellows.įilm grain also gives a greater impression of sharpness even if there is diffraction softening, although artificial sharpening in digital photography is easy to do but is often underutilized, especially by beginners.Īnother obvious issue is that modern digital photographers frequently examine their images at 100%, and so may be much more sensitive to diffraction than was common in the day when only a loupe was used on film negatives, and when prints were evaluated at a reasonable distance.Ī grain magnifier was used when printing, to get critical focus. You can still apply movements with the right equipment. Old cameras had tricks to maximize depth of field which are no longer available to us today with digital photography: the large bellows cameras allowed the lens to be adjusted independently of the film, with tilts, which allowed skewing the plane of focus which allows for a lesser aperture setting than otherwise would have been needed. Or maybe they are trying to maximize depth of field - often far more than needed - without an understanding of the limitation due to diffraction. I see a considerable number of beginners on these forums using f/22 on an APS-C or Micro Four Thirds cameras when shooting landscapes, perhaps because that is an f/stop used by the old references. Especially if they learn photography from old books where medium- or large-format photography is assumed, they may very well use aperture settings far tighter than their sensor sizes and subject matter require.

Many advanced beginner photographers may learn about the use of aperture in depth of field and the hyperfocal distance technique, but they may apply them poorly. He was a founding member of Group f/64, which as the name suggests, promoted the use of great depth of field in images, but f/64 on an 8x10 inch negative is only equivalent to f/8 or f/9 on 35 mm, which is less than many routinely shoot when doing landscapes, and that usually doesn't generate too much diffraction. At any given f/stop, the effects of diffraction are going to smaller as a percentage of film width with a larger format.įor example, Ansel Adam's most famous image of Half Dome was taken at f/22, but the film size was so large that it had about the same amount of diffraction as would a 35 mm sensor at about f/4.

I'm not sure that diffraction was as much of an issue with film photography as it is today, and a few reasons pop into mind:įilm cameras historically used larger formats than modern digital sensors, with smaller film formats only becoming fashionable towards the end of the film era.

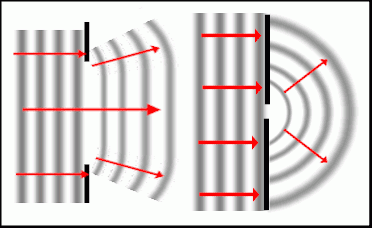

The setting can be saved as a component of a Custom Preset and applied to multiple images onwards.I'm wondering how strong a sharpness-degrading factor lens diffraction would be in a film camera?.From the Lens tab, enable Diffraction Correction with a checkmark to apply the correction.Go to the Lens tool tab and select the Lens Correction panel.Select an image or multiple images from the browser.Note that this feature is compatible with RAW files only. Enabling this tool and the application of Sharpness Falloff correction can be considered as the first stage in capture sharpening. When the time comes to output files, it extends processing times. Note that this feature is not enabled automatically as it is processor-intensive when images are viewed at 100% magnification. Selecting this option helps to mitigate the effect using a sophisticated deconvolution algorithm to sharpen the image and restore some of the fine details that were lost during capture. Stopping down beyond that point will only reduce the resolution.Ĭapture One’s Diffraction Correction option enables you to close down at least one step further than you would be able to do so without it. Diffraction reduces micro-contrast first and then resolution as you stop down beyond a certain aperture, which is known as the diffraction limit. Overcoming diffraction is challenging for photographers trying to maximize sharpness through the use of extended depth of field, and it is especially burdensome in close-up work and landscape photography, where small apertures are crucial.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)